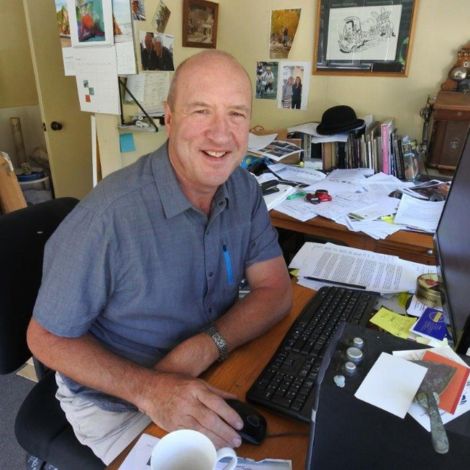

In 1992, Lakes District Museum & Gallery Director David Clarke wrote a speech about 'the day in the life of a small town Museum Director', which he presented at the Museum Aotearoa National Conference. His speech reads like a personal diary entry, and we feel privileged to share a snapshot of this moment in history from almost 32 years ago.

David has recently retired as Museum Director, after 34 years of being busy. To name only a few of his achievements, David has been responsible for raising millions of dollars for the arts, has provided a home to over 180 exhibitions, and has saved a number of historic buildings in the district. Let's just say David has more than earned his retirement.

So go on - grab a cup of tea, sip back and enjoy this slice of history.

A Day in the Life of a Small Town Museum Director

By David Clarke, written in 1992

I drive up the hill into Arrowtown, that idyllic little town tucked away from the prevailing wind, nestled beside the wide river flats of the Arrow River, where it fans out after its steep turbulent descent through narrow gorges from its sources up near Macetown. The suburbs now stretch out along the ridge that was once grain fields. The signs of building are everywhere, as the town continues to grow at one of the fastest rates in New Zealand.

It’s a beautiful spring morning- snow is still heavily caked on Coronet Peak and the back of Cardrona. It would be nice to enjoy a bit of spring skiing, but that will have to wait. I will be too busy to contemplate that.

Up the hill, and past the first of the preserved buildings that Arrowtown is renowned for. The powder magazine was built in 1877 for $90, providing safe storage of explosives for individual miners, for $2 per annum. Miners had flocked here in 1862 when gold was discovered in fabulous quantities, several hundred metres from the town.

To the left are the giant Wellingtonians flanking the gates of the Presbyterian Church. Huge trees, over 50 metres tall. I am sure incoming flights heading towards the airport at Frankton use them as navigation aids. The church is a delightful example of stonework, built in 1873 using Chinese labour. It is dwarfed by the trees, whose roots were slowly consuming it until a solution was found earlier this year, and a trench was dug around the church and filled with concrete.

I go on past the wooden Anglican Church of St. Paul’s. Simple but elegant. Like the Presbyterian church, it was built in 1873, but this time made from timber from the head of Lake Wakatipu. Painted in cream with its bright red roof, it is bathed in the first sun as it rises over the ridge behind the town.

Down the sweeping Ballarat Hill, past Sandy’s house, lovingly restored out to the ruins of the Ballarat Hotel stables. The smell of fresh bread and croissants is permeating out of Lieber’s Bakery. I look across Butler Park and see that the Lions Club have done some more work on the restoration of the Police Camp building. Shifted to this site two years ago, the Police Camp building was saved from decay and vandals and now nestles in the shade of the river bank willows. Built in 1863 from red beech pit sawn and shipped from the head of the lake, I thought it was worth saving. I thought it would make a good interpretation centre for wooden buildings. It looks right in place now.

Around the tight corner into Buckingham St is where it all began. Several shopkeepers are out sweeping their frontages, much like they've been doing for 130 years. The starched aprons are gone, and names like Cotter’s Store, W Jenkin’s, and Pritchard’s Store, which served the miners and generations of rural people, have given way to the Golden Fleece, the Old Smithy, Coachman’s Store and Arrow Stores. They now serve the tourists, farmers, young families and the retired population, who have come for the sun, tranquility and activity of the Garden Club, the Horticultural Society, and the Travel Club. They've never been busier.

The unloading of a beef carcass into the butcher's shop and the North's bread truck blocking the street at the Coachman’s remind me that this is no tourist facade, no Hollywood set, but a live working town and active community of 1,000. The main street buildings are in keeping - Arrowtown’s strict building code ensures that. Many are original or contain the foundations of the original buildings.

The stone stables of Bendix Hallenstein are now a restaurant. The New Orleans Hotel, the craft shop in Bill Murphy’s old blacksmith shop. The Gold Nugget in Adams store and on past the museum, partly housed in the majestic, former Bank of New Zealand building - the grandest in town. It’s a pity the additions of the 1970s with its Hardie plank frontage and somber grey paint provide such a poor companion. However, a new paint job when the weather warms up will improve things.

That reminds me, as I park at the back of the museum - I must get onto a builder to make a start on the new rear entrance. It’s our welcoming face to most visitors, on the sunny side of the street with views of the river. The stone-walled seating and easier access to the museum will be great improvements.

I guess today will be just as frantic, and we are still in a quiet time. The museum was founded in 1948, in the slightly incongruous location of the old billiard rooms of the Ballarat Hotel. This so-called symbol of misspent youth. The Museum has gone from strength to strength, shifting in 1955 to the BNZ building, and under a series of directors, controversies, and expansions, it now has a fine reputation and an annual patronage of around 50,000 visitors.

I came to the job via a History degree, years of travelling, hospital orderly, landscape gardening and building. I’m not sure this critique is what Museum directors are made of – but the AGM was last night, and generous praise was given. A lot has been done in my 3 years, but there is so much more to be done.

The phone is already ringing when I come in the door. Behind me, across the wide verandah of the Mary Elizabeth Banks Wing, I hear the sound of mass footsteps as the first tour of the day arrives. Japanese visitors, their guide explaining everything – hilarity as they look at a Victorian moustache cup, always a source of mirth amongst Japanese. The phone call is from the Queenstown Promotion Association. They have a Mr Brazil, an Englishman from Singapore, who wants to know about the Chinese in Arrowtown. He writes for the Straits Times. 11.00am? – sure, I’ll show him around. He is just one of the many journalists, photographers, film crews and tour guides that I will show around the Museum and the town during the year.

My next job is to change some bulbs in the gallery. Our newest wing always looked like it should have some artwork displayed.

Raised in Invercargill, I always enjoyed the Southland Museum with the intermix of art and artifacts. It provided change and impetus for new audiences. A sea of dour Victorian portraits never appealed to me, nor to most of our visitors. Nine months ago, we started showing NZ art.

The artwork is mostly contemporary – not everyone has liked it, and the latest show from Jonathon Jansen Gallery, with its Banbury’s, Morrison’s and Dawsons, is more challenging than most. But it has been educational, has created discussion, and our next three shows will be more ‘mainstream.’ A new wall blocking off the toilet doors and providing more exhibition space has transformed the gallery. The Southern Regional Arts Council has been supportive here with funding.

Visitors come and go. ‘The Street’ is starting to liven up. It’s a perfect day now. A lady researching a documentary is after information on a Mr Chan, a Chinese Herbalist. I escort her into our research room, cramped and overflowing and pour through the sources. The room didn’t exist 3 years ago, but along with Aaron, the history student I employ in the university holidays, we have collated, catalogued, copied, and now have the basis of a valuable research tool. So much has left the area. Microfiche, papers, photos and books provide answers to the never-ending riddles as people scan newspapers and obituaries, birth notices and marriages. Like amateur detectives hoping to solve the fate of Great Great Grandfather McBride – farmer. Or Greta Aunt Sarah – hotel keeper.

Our 6,000 photos are now in wax boxes and acid-proof envelopes. Volunteers come to index minute books and newspapers. Shelves are filled with cassettes from our ongoing oral history programme, Task Force Green is helping here. I started taping with a hiss and a roar, enjoying the tales of Harvey, the last boy to live in Macetown; Daisy telling of her first dance and her trips around the district with her brewer father; of Duncan and his days in Skippers; of Joe, the worse for weather trying to hitch a ride home on the night cart, and being told there was enough of his type on the back already; or of lashing sluicing pipes together and rafting down the rapids of the Shotover, when now they do it in rubber rafts. Inner-most secrets are revealed, a tear is wiped away.

The trip to Hugo Manson and Judith Fyfe’s oral archives in Wellington got me motivated, and now as time gets to a premium, both with me and the subject matter, I’ve encouraged others to help.

Eureka! I’ve found it in Neville Ritchies’ thesis ‘Archeology and History of the Chinese in Southern New Zealand’. Mention of Mr Chan. The film lady leaves pleased, putting a donation in the box as another tour arrives, pouring over the books displayed for sale in our foyer area.

The commercial reality has seen this area expand into a sizeable share of our revenue. Several backpackers are looking at maps and asking staff about walks in the area. Macetown low track has 23 river crossings each way. Your feet will be numbed into submission by the snow-fed water. The Big Hill Track will be beautiful today, or perhaps Sawpit Gully, with stunning views to the south out over Lake Hayes. Any cheap accommodation, they ask. Can we hire mountain bikes? Where’s the Bungy Bridge? How far to Coronet Peak? All answered. We are the Information Centre for the town.

I answer another phone call – Northern Southland College, Form 1 and 2 – can they come in October? I book them in, one of the 30 schools that visit each year to take advantage of our Education Programme. I do a museum tour and mining methods. Ray Clarkson, a retired teacher from Invercargill, ambles from building to building, telling stories from the past through the main avenue of trees – more ash, oaks and elms, planted in 1867. The Mary Cotter Tree, danced round by the young Mary when it was planted, past the row of wooden miner’s cottages, buckled and twisted from the exposure to years of sun and frost, much photographed, seen on endless calendars and postcards. On to the gaol, the churches and the cemetery. William Colville, drowned in the Shotover 1864, aged 34 years. Robert Lawson, miner 1864, bronchitis. John Robinson 1864, aged 11 weeks. Everyone tells a story.

I go down now to the Chinese Village where Nick Clark of DOC will paint a picture of Ah Lum, Ah Nue, Old Tom and Tin Pan. It’s the ‘Clarke, Clarkson and Clark’s Tour, and the children really enjoy it. Tomorrow, it will be the Kawarau Mining Village and the Bannockburn sluicing for them.

Back at the Museum, Mr Brazil has arrived – a Cockney hardcase, with an endless string of questions. “Who owns this town?” Another one who thinks it’s a mock-up like Shanty Town. “Can we go to the gaol?” I tell him of the blaze of colour in autumn, of the festival with its market days, singing, dancing, plays, barber shop quartets. The celebration of a town, and of the input of the Museum in holding the festival Art Exhibition, and this year, a Country Day at Millbrook. A day where 2,000 locals enjoyed old-fashioned cricket, farm machinery, horse races, and sheaf tossing under royal blue autumn skies.

I lock him in a dank, cold cell, without light. Cells that would have seen a thousand drunks, claim jumpers, gold stealers, swindlers and carpet baggers. He loves it. Camera clicking, we head for the Chinese Village and stroll amongst the willows, dew still lying in the coldest part of town. We contemplate the lives of single men, seeking their fortune in far-off lands, living in tiny huts with their opium, fantan and pakapoo, dying in obscurity, shunned by the Europeans, and never returning to the ‘Flowery Land’, rich heroes.

Back along the main street, shopkeepers talk outside the front shops, relishing the warm spring sun that now bathes the street and herald the end of permafrost and burst pipes.

I leave Mr Brazil and drop into the Post Office. ‘Post and Telegraph’ it says out the front, as it has for years. Apparently, it’s the only Post Office allowed to say this, but that didn’t stop NZ Post ‘divesting’ it almost two years ago. “It won’t pay”, they said. Concerned with the loss of the Post facilities, and more importantly a loss of a listed building that has always been part of the streetscape, the Museum offered to run it.

We negotiated a peppercorn rental, told the locals to use it or lose it, cut hours in the quiet winter months, and employed a cheerful efficient postmistress. This last year we made $10,000 profit. Perhaps not the role of a Museum, but when the Museum is a focal part of the community, it seemed the right thing to do.

Time for lunch. I make it a policy to go home, away from the phone questions – a breather. Down McIntyres Hill, looking out to the blue glass of Lake Hayes, trees and mountains, imaged in its perfect reflection. This afternoon I must get some more display work done, get into some of those little jobs that had been nagging for weeks. I don’t come in after work and rarely in the weekends. I’ve heard of Museum Director ‘burn-out’, and can see how it happens.

Back into town, I drop into Phil’s place. A jovial ex-mechanic, he is restoring our 1923 Fordson Tractor. He has already done up our 1932 Massey Harris 4WD and enjoys the challenge. Can you get a new bearing for the front wheel? Have you got those kingpins yet? I make a mental note.

Phil’s one of several volunteers. Geoff likes horse-drawn vehicles. He will do some more on the Stanhope Buggy when he’s planted the veggie garden. Ray’s a retired electrician and is working on a Pelton Wheel Generating Plant.

The underneath of the Museum is littered with agriculture machinery. What do we do with it? It’s been here since the Centennial of 1962. Discussions continue with the development of a small Agriculture Museum on the Millbrook Golf Course development at the edge of town. Something that will tell the history of the district’s agriculture, when oats and barley grown on the Crown Terrace were the best in the world. The Museum’s machinery needs to be in a rural setting. Townspeople are nervous about a multi-million-dollar complex on their doorstep. What will it do to the town? Do we need it? – You can’t stop it, it's already half completed. Let’s work with them and ensure the historical integrity and flavour are kept intact.

Back at the Museum, a post-lunch lull allows me to open mail. Seemingly endless, my desk – in organized chaos – is awash with paper. The photocopier whirrs, the typewriter clatters as Lyn completes some correspondence. Bills I glance at before filing. Three more genealogy enquiries, tour bookings. I write a couple of letters, one concerning rumoured cuts in council funding – what else is new. Another to a lady in the North Island seeking those family clues, telling her there will be a research charge in the days of ‘user pays’.

It’s on with the overalls for a couple of hours, working on a display depicting the history of hotels. Will it ever get finished? There is always interruptions. – No interruptions please Lyn: no Mr Smith with a sewing machine or a tobacco cutter that’s at least 100 years old, (we have 20 of each already); no John and Peter with the remains of a rusty shovel and chain found by the river as they fossick (like I did every Xmas holiday at Whitechapel, hoping to find a nugget under every rock); no advertising people selling you a spot on the Jasons Map or the Guide to Golf Courses in New Zealand, that will (they tell you), increase your business three-fold for only $450 + GST.

Out with the tools – a wall here – some old shingles here – this would look good – my imagination running riot. I find this part hard, to make a display that will entertain, inform and educate people of all ages and races.

Late afternoon I pack up. I notice the floors downstairs need a strip and polish. I must get onto the cleaner – another mental note. I return a few phone calls. The visitors are few now. I’ll have to go to Queenstown tomorrow to pick up some more materials for the hotel display.

The days are drawing out – the willows have sprouted in the last few warm days. Soon they will block our view down to the river, but now I can see people walking a dog, and small boys with pans and dreams of making it rich. It will soon be mid-summer, and the hordes will arrive – ‘hoons’ from Dunedin and Invercargill, cruising the main street, stereos blaring, sleeping in car boots, pulling out plants in the window boxes and hanging baskets I’ve lovingly tended around the Post Office and Museum as they wait for New Year's Eve. Then they will be gone, leaving a sea of empty beer cans.

I’ll be gone too for a few days. Into the hills amongst the smell of thyme and rosehip, the dust and dry air, and the crackle of exploding broom pods. In amongst the canyons of the Arrow, Fews Creek, or Skippers Creek, camping by the old hotel at Bullendale, swearing you could hear the honkey-tonk piano and breaking glass in the middle of the night. I will marvel at the power dynamo on the left branch of Skippers Creek, or the stampers at Andersons Battery in Macetown. How did they get machinery that size up there? Nowadays, they would use a helicopter – not horses, sledges, blood and sweat. Armed with a camera (I’m on a field trip you know) I’ll poke and fossick, maybe even wash a gold pan or two.

5 o’clock now – people amble into the Royal Oak, to stand around the last fires of early spring. To talk of lambing and spring, skiing and work. A handful of shops stay open, there’s always a late tour bus or two. Our day is over, the day’s takings are put away, the lights are out and alarms are set.

It’s been another typical day at a big museum in a small town. Tomorrow will bring new challenges, but for now, I must get home. I’ve got a talk to give at the Museum Conference, and I haven’t a clue what to say.

Postscript, November 2023

"As I have just retired as the director after 34 years I look back and reflect on how little has changed yet so much. We still welcome 50,000 plus visitors, still run the information centre, art gallery and bookshop, though we now also own and run the Arrowtown Post Office. We have a full-time educator who, with her team, welcomes 4,000 students a year from throughout New Zealand. We are truly the repository for the district's taonga.

"Our purpose-built archive facilities are run by a part-time archivist, and we now have a magnificent collection. We have just completed a $3.5 million earthquake strengthening and restoration project on the bank building, and over the years, have built new and engaging displays.

"I have worked hard to save a number of heritage buildings in the district which gives me huge satisfaction. The gallery has curated over 180 exhibitions, helping to support local artists. I stopped going home for lunch years ago, and have ended up working endless hours every day of the week.

"But that’s life as a Museum Director, and I've loved every minute of it."